Fiction

Scientists vs. Machines

A psychological thriller for the AI age

The MANIAC

by Benjamin Labatut

Penguin, 2023 ($28)

Blending fact and fiction, Chilean novelist Benjamin Labatut's century-spanning history of the rise of AI explores the minds of the scientists who dreamed of machines able to learn, evolve and self-replicate without human guidance. It also tells the stories of the scientists who feared this kind of progress.

Count among them Austria's Paul Ehrenfest, “the grand Inquisitor of physics,” whose terrors drive the novel's brisk, wrenching first section. (Later sections cover Hungarian-American mathematician John von Neumann, inventor of game theory and of the world's first programmable computer, and an account of master Go player Lee Sodel's five-game face-off against the AI program AlphaGo.) At the 1927 Solvay Conference, as great thinkers debated quantum mechanics and its implications, Ehrenfest, in Labatut's formulation, felt that the world had become less solid. He “could not shake the feeling ... that a fundamental line had been crossed, that a demon, or perhaps a genie, had incubated in the soul of physics, one that neither his nor any succeeding generation would be able to put back in the lamp.”

Labatut covers the rest of Ehrenfest's tragic life in a headlong gush, making it a kind of psychological thriller. The prose grows feverish as the Nazis seize power, and the scientist, finding it impossible to keep up with developments in physics, spirals toward an outcome the opening pages establish as inevitable: his murder of his own son and his death by suicide. Reasonable readers will arrive at varied opinions about the taste of all this—the facts are the facts, and the narrative pulses with empathy, but the tone at times resembles cosmic horror, as if Ehrenfest were a Lovecraftian naif driven mad after glimpsing an Elder God.

Or perhaps that's perfectly appropriate. The von Neumann section, constituting the bulk of the book, is blessedly lighter. Labatut draws in a host of voices—von Neumann's wife, children, colleagues, rivals—to tell the story of the development of a brilliant mind but also of reason as “the destructive influence” that the novel's fictional Ehrenfest so feared. Von Neumann is “searching for absolute truth, and he really believed that he would find a mathematical basis for reality, a land free from contradictions and paradoxes.”

Once von Neumann, a Jew, has fled World War II Europe for the U.S., Labatut hastens the narrative toward the locus of so many stories of 20th-century science: the Manhattan Project. The jolt here is that for Labatut's von Neumann, the development of the nuclear bomb is but a step on the path to the technology with which he hopes to truly change the world: computers that think. In the early 1950s von Neumann developed his first attempt at such a machine, MANIAC I.

A note here about Labatut's technique in crafting this intimate and, of course, subjective fiction: The story is drawn from fact but also engineered to make a case. Again and again in his work, scientists at the edge of what's possible—and often the edge of sanity—change our world in ways they couldn't have anticipated. Labatut pioneered this inner-life-of-the-scientists approach in his celebrated 2020 novel When We Cease to Understand the World, which tracks, among other fascinating subjects, the breakthroughs among well-intentioned chemists and others that eventually gave the Nazis instruments of mass murder. (Einstein himself worries in that book that in response to quantum uncertainty, a “darkness would infect the soul of physics.”) The 2021 English translation of that novel, originally written in Spanish, was a finalist for both the Booker Prize and the National Book Award. The MANIAC is the first he has composed in English.

Labatut bluntly states his themes in the voices of the luminaries who narrate his chapters. Here his version of physicist Eugene Wigner declares, “It seems the ever-accelerating progress of technology gives the appearance of approaching some essential singularity, a tipping point in the history of the race beyond which human affairs as we know them cannot continue.” (Labatut also attempts the inimitable voice of Richard Feynman, who, like most of The MANIAC's narrators, favors paragraphs that can stretch on for three pages.)

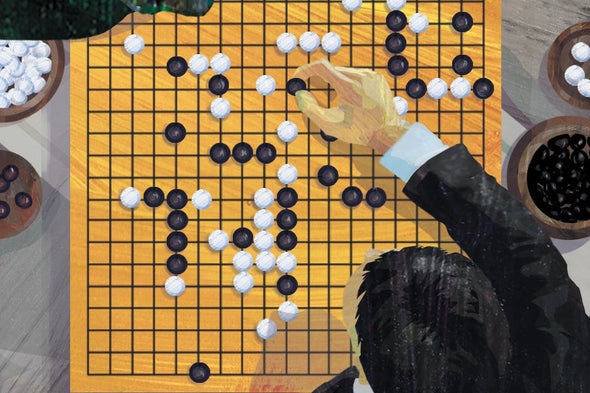

The novel's final section, a thrilling human-versus-machine matchup, points to what von Neumann had wrought—and reflects the warnings of Labatut's Wigner. Although its science never strays from what's been reported in the real world and although Labatut honors the discipline of historical fiction, The MANIAC qualifies as science fiction, at least as practiced by Mary Shelley and her adaptors. Neither Shelley nor Labatut includes in their work a scene of a scientist shouting, “It's alive!” as some cursed creation lumbers to life. But the warning of that moment powers The MANIAC as surely as electricity enlivened Frankenstein's monster, a breakthrough who, in every telling, boasts the capacity to break us. —Alan Scherstuhl

Alan Scherstuhl covers books for a variety of publications and jazz for the New York Times.

Nonfiction

Seductive Toxins

A different side of nature's gifts

Most Delicious Poison: The Story of Nature's Toxins—From Spices to Vices

by Noah Whiteman

Little Brown Spark, 2023 ($30)

We might not realize it, but we routinely welcome poisons into our bodies—they are in our tea, our wine, our spices, our medicines. It's easy to discount their toxic potential and instead focus on the myriad ways they make our lives better. Biologist Noah Whiteman's exacting yet expansive analysis reminds us that although they “permeate our lives in the most mundane and profound ways,” the toxic chemicals we use every day are not nature's gifts to us but rather its munitions.

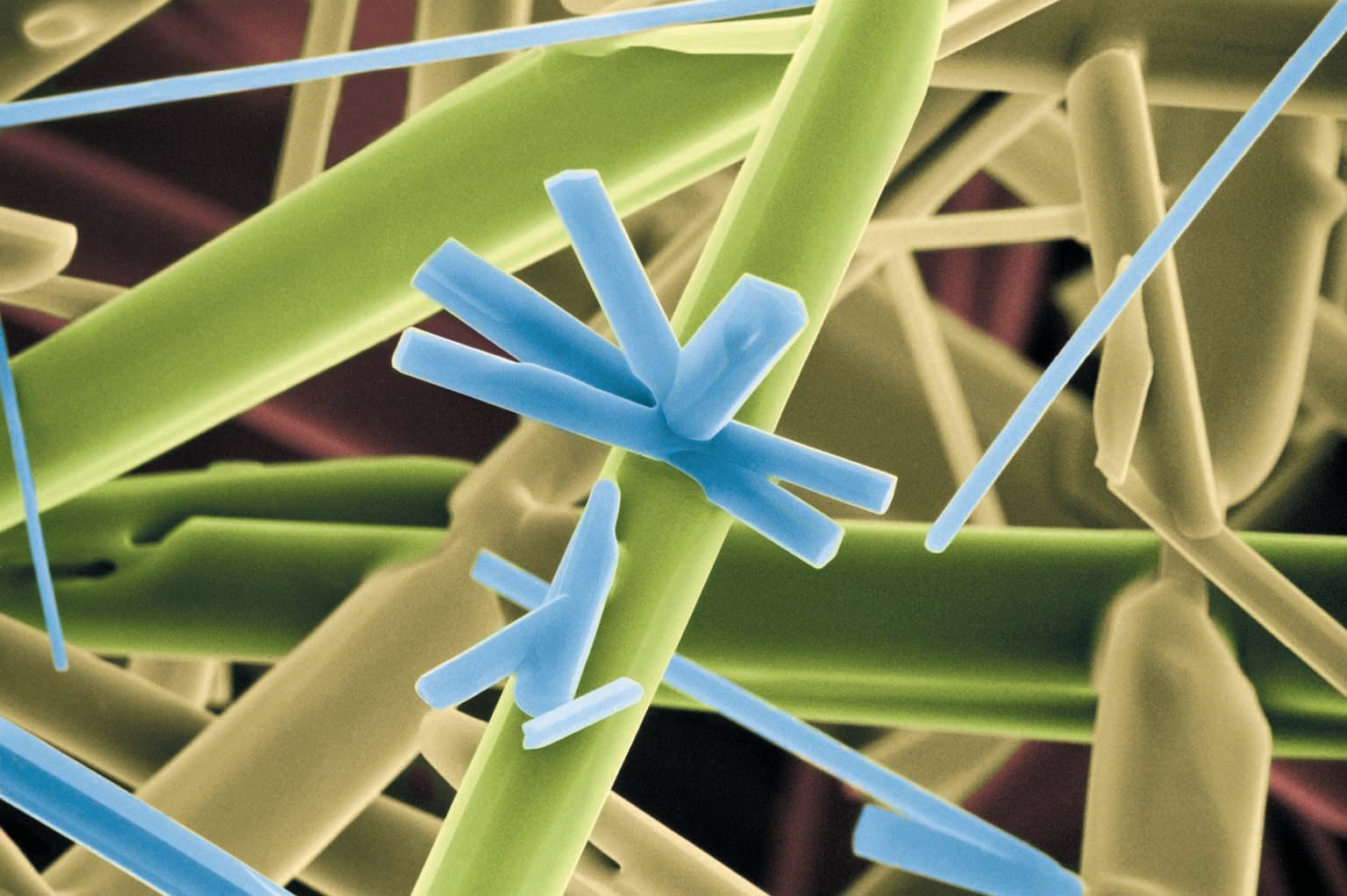

These weapons were forged during an evolutionary arms race that raged on well before humans existed. Plants developed toxins to defend themselves from predators. Predators in turn adapted to those toxins to gain an advantage in their fight for survival. But at our earliest opportunity, humans also sought to profit from these substances: scrapings from a Neandertal's teeth show traces of toxins that held medicinal value, including the bases for aspirin and penicillin. Today we routinely find ourselves “threading the needle,” Whiteman writes, to leverage the advantages nature's toxins offer while avoiding their bad effects.

This tour of the world's toxins includes obvious candidates such as cocaine and nicotine but also substances less likely to be viewed as poisons: quinine, caffeine and cinnamon. Whiteman's analyses toggle between the micro and the macro, detailing each one's chemical makeup but also charting its external impacts.

For example, our bodies convert the myristicin in nutmeg into a psychedelic amphetamine that, in sufficient amounts, can be used as a narcotic. Historically, nutmeg's supposed medicinal properties (it was considered an important ingredient in the treatment for plague, although it didn't work very well) made it such a valuable spice that the Dutch traded Manhattan to the British to maintain access to its production.

Although Whiteman's approach is rigorous and often technical, his style is engaging, and his work becomes especially poignant when he discusses his father's death from alcohol use disorder and how grief fueled his research into ethanol's toxic hold over so many. As we patronize nature's dangerous pharmacy, we must “walk on a knife's edge between healing and harm.” —Dana Dunham

In Brief

Eve: How The Female Body Drove 200 Million Years of Human Evolution

by Cat Bohannon

Knopf, 2023 ($35)

Struggling to see how deeply ingrained patriarchal thinking is in science? Look no further than studies of animals and humans. For decades it was acceptable to exclude female subjects entirely (because of their menstrual cycles and the chance of pregnancy). Eve uses this maddening lesson as a jumping-off point to tell an alternative evolutionary history of our species. We meet extinct matriarchs such as Donna, the squirrel-like progenitor of live birth, and Ardi, who was the first to walk on two legs. Exploring human anatomy through the female body is a refreshing change in perspective, and readers will gain a fuller appreciation for “women's bodies, from tits to toes.” —Maddie Bender

Christmas and Other Horrors: A Winter Solstice Anthology

edited by Ellen Datlow

Titan, 2023 ($27.99)

Editor Ellen Datlow collects diabolical tales embracing winter solstice, the shortest day of the year, when cultures around the world conjure sinister stories of vengeful spirits. The burning bones of a wood demon in a Finnish sauna reveal the emptiness of a future son-in-law. During the apocalypse in the cold of Quebec, a woman comforts a monster who eats the violent and the cruel. Thieves practicing the Welsh folk tradition of Mari Lwyd encounter two resurrected 19th-century highwaymen. The theme of hubris—of people oblivious to impending tragedy and superstition—heightens our fascination with folklore spirits that manifest as catalysts for reflection and change. —Lorraine Savage

Alfie & Me: What Owls Know, What Humans Believe

by Carl Safina

W.W. Norton, 2023 ($32.50)

It won't take long to feel enamored of the newly adopted member of Carl Safina's family: a baby screech owl. A beloved science writer, Safina presents accounts of Alfie's growth, eventual release and even motherhood that show tender concern for Alfie's quality of life beyond mere physical benchmarks. Don't expect a dramatic, sensational plot; here the quiet message is that nature doesn't need to serve us humans beyond existing for itself. Safina's humble sense of wonder and his appreciation for Indigenous practices and knowledge combine in a joyful celebration of not just Alfie's adoption but the interconnectedness between nature and humans. —Sam Miller