NASA has a planet-sized problem on its hands.

Ironically, the source of this is here on Earth: Congress, which has the penny-wise but pound-foolish policy of trickling out space agency funding every year, hobbling many of NASA’s mission goals that require thinking past the usual two-year House or six-year Senate term. This has repercussions that can be felt across the solar system.

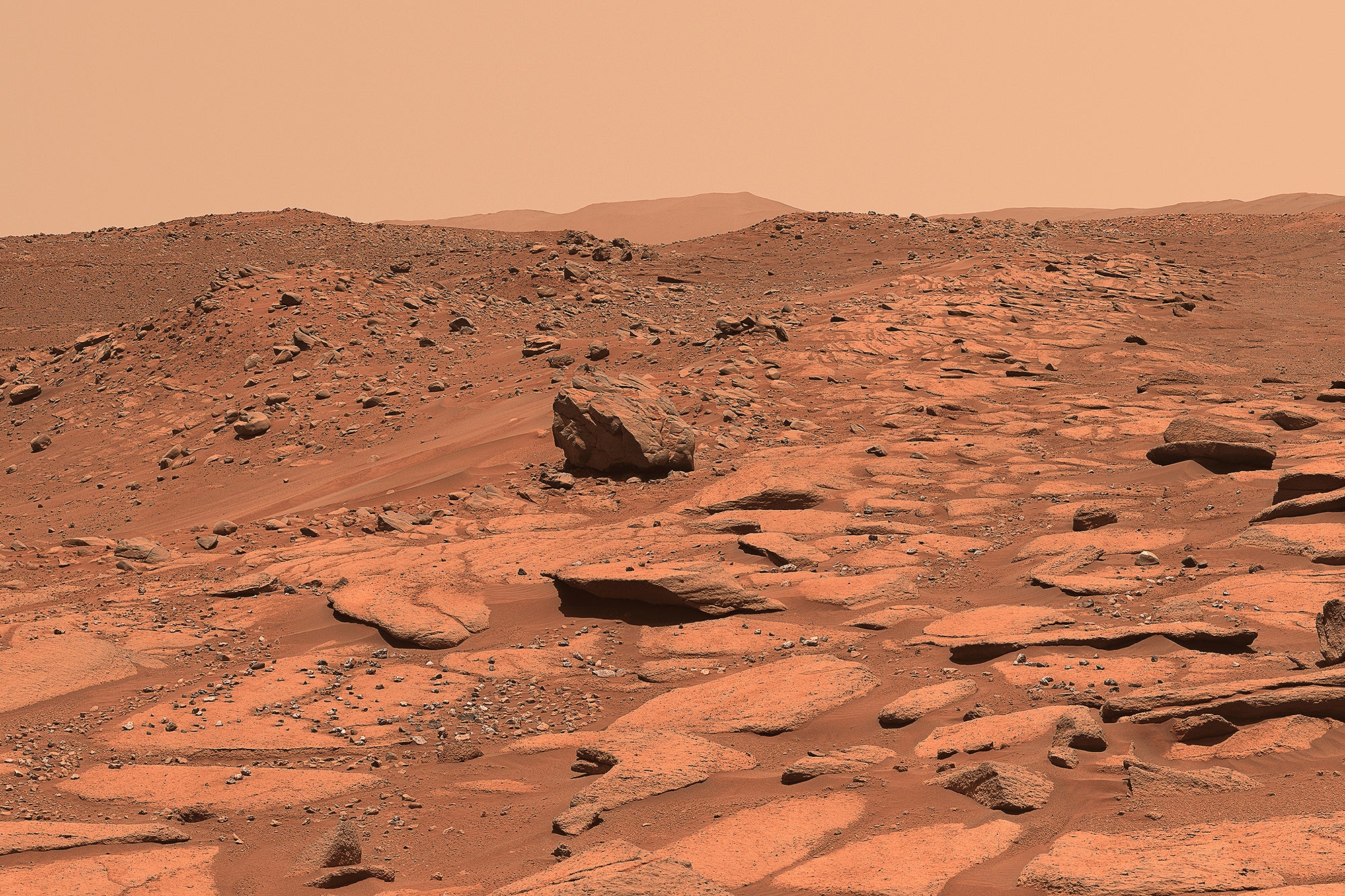

Right now on Mars, the Perseverance rover is collecting small samples of the Red Planet, gathered from inside the 45-kilometer-wide Jezero crater that once held a huge lake, billions of years ago. Scientists consider it one of the best places to scout for evidence of ancient life on Mars, or at least see if conditions were ripe for its genesis.

These Martian souvenirs safely rest inside hermetically sealed cylinders, either stored on board or dropped in strategic locations. A future Mars-bound mission will pick them up and bring them to Earth for study.

The problem? That return mission currently does not exist.

And it’s not clear when it will, either. In September, an independent review board investigated the current state of a Mars Sample Return (MSR) mission, and found there’s a “near-zero probability”—tech-speak for “no way”—for it to be ready for launch by 2028. It could meet a 2030 deadline, but at a cost of $10 billion, which would make it among the most expensive science projects NASA has ever undertaken.

But it’s a vital part of NASA’s plans.

The 2011 National Research Council’s Planetary Science Decadal Survey, created by a panel of dozens of leading scientists, stated that MSR is a “highest-priority flagship mission” for the 2013–2022 decade. An earlier 2008 NASA preliminary planning document reported that of 55 important investigations into Mars, half would be addressed by MSR. It’s not hard to see that looking into the idea of life on Mars, ancient or extant, would be a critical scientific goal for NASA, and one with a potentially immense impact on all humanity.

The first part is already underway. A decade-old Mars 2020 Science Definition Team report stated that using the Perseverance rover to collect samples from the planet’s surface would lower the cost of a future MSR mission. “Any version of a 2020 rover mission that does not prepare a returnable cache would seriously delay any significant progress toward sample return,” it noted. Heeding that advice, Perseverance was designed to collect those samples and has been doing so since 2021. Now comes the hard(er) part: returning them to scientists on Earth.

Until very recently, the plan was to use Perseverance itself to bring the collected samples to a suitable landing spot. While this would take time away from its exploration (and, more worrisome, would run up against the expected life span of the rover) it’s likely the safest and easiest method. Certainly, the most cost-effective.

In the meantime, NASA would build a lander and a Mars Ascent Vehicle (MAV), a rocket that would take Perseverance’s samples into Martian orbit (The lander would come equipped with two sample-carrying helicopters based on the successful Mars Ingenuity ‘copter as a backup if Perseverance couldn’t complete the task). From there, a European Space Agency Earth Return Orbiter mission would rendezvous with the MAV, ingest the sample container—literally opening and “swallowing” it—and then bring it to Earth, where it would land in the Utah desert like the recent OSIRIS-REx asteroid Sample Return Capsule.

However, the 2023 independent review board put the kibosh on that, finding that this mission cannot be accomplished in the needed time frame for the available budget.

In essence, NASA has to start all over again planning MSR. The good news is that work on this has already begun, and the space agency hopes to have a new mission concept early next year.

It’s easy to point fingers at NASA for the cost overruns and schedule delays, but to be fair, the agency played by all the administrative rules. That’s not to downplay mismanagement issues, which the independent review report pointed out in detail, but which, honestly, can be expected for huge projects across multiple divisions in a government agency. Committees met, ideas were debated, reviewers reviewed, and the best plans advanced. Then reality intruded. Getting to Mars is hard. Many missions never make it. Adding the incredibly complex technical issues of not only getting back, but doing so after a complicated orbital rendezvous, makes matters more than twice as hard. Just getting from the Martian surface to orbit is ridiculously difficult, and the important NASA requirements for testing and redundancy—in the case of the MAV, at least—make it all but impossible under the current plan.

Where does this leave the mission? Well, MSR could be canceled, but that is clearly the worst possible option. Given its importance scientifically—and, with all the time and money already invested, as well as the efforts undertaken by Perseverance—this isn’t something to be considered realistically. NASA could trim MSR’s budget, cutting costs, but at this point doing so in the current plan would do more harm than good. There’s no science being done with MSR, so all the engineering is geared toward picking up the samples and getting them to Earth; cutting any of the tech needed to do that could jeopardize the mission.

So here’s my radical thought: Fund it. Fully. Give NASA what it needs to make this mission work, including a wide enough margin for technical safety given the difficult nature of the engineering and management.

By funding it, I don’t mean robbing Peter to pay Paul as has happened to other NASA missions that ran over budget, taking needed money away from other deserving space agency endeavors. I also don’t think simply making it a separate line item in NASA’s budget, as was done with the James Webb Space Telescope when its costs bloated, will work either. It might suffice for this particular case, but it is not a long-term solution for NASA’s goals.

The basic issue here is that NASA’s funding is a zero-sum game, so cost overruns in one mission will necessarily impact others. But that game of shuffling money wouldn’t be so dire if NASA very simply had a bigger overall budget. This would also fix many of the management problems pointed out in the 2023 MSR report, allowing NASA to hire more technical and administrative staff for the job.

This actually shouldn’t be controversial. Public perception of NASA’s funding is hugely exaggerated over its actual budget; in one 2018 poll the average American thought NASA received over 6 percent of federal spending, when in reality NASA gets only half a percent. Given the amazing achievements NASA accomplishes with this tiny slice, a dedicated effort to correct this misconception would make the political struggle of increasing the space agency’s funding much easier.

From a strictly economic point of view, NASA returns far more money than is given. The agency has estimated that it generated economic output of $71.2 billion in 2021; that puts its return on investment at something around $3 for every dollar put into it. And, of course, we get far more from NASA than simply economic benefits.

We don’t spend money on NASA; we invest it.

In general, NASA’s science and exploration enjoys broad bipartisan support. This is especially remarkable in today’s political climate, where it might be hard to get the two parties to agree on the time of day, and where the Republicans have a history of trenchant antiscience stances—especially when it comes to climate, a field of science NASA heavily supports.

Increasing NASA’s budget should be a no-brainer. Instead, though, Congress has a history of targeting NASA whenever a budgetary ax is wielded. This makes zero sense given how small a portion the agency gets; the amount of money the Department of Defense wastes every year is comparable to NASA’s entire annual budget. Cutting NASA’s budget is like making room on a computer’s hard drive by deleting tiny text files while ignoring the gigabyte movies you’ve already watched.

Please note I’m talking about what we ought to do—that is, if politicians in charge of NASA’s funding lived in the real world. That may be a stretch with a Republican-led House of Representatives that had trouble electing a speaker—and earlier this year proposed bludgeoning NASA with a 22 percent cut that would kill MSR, end moon landings and lead to 4,000 layoffs. Perhaps if the public were more vocal, and it were an election year, Congress might listen. Might.

A monkey wrench in all this is the bipartisan Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023, which became law in June to thwart the federal government defaulting on its debt. Part of the fallout from this Act means NASA’s budget is capped until ’25. This already has had an impact, as NASA officials are considering cuts to Hubble Space Telescope and the Chandra X-ray Observatory, two of the space agency’s workhorse observatories. Increasing the budget for MSR is essentially impossible as long as this act is in effect, and the uncertainty in the funding makes it difficult for NASA to know exactly how to move forward on any new designs.

If MSR—and NASA itself—can weather these setbacks for the next two or three years, they may yet find a path forward. Despite all this cacophony, the argument that increasing NASA’s overall budget still stands. Boosting it by, say, 20 percent, so to $30 billion per year, would ease a vast amount of pressure the agency feels when proposing and building new missions. Even doubling its funding would hardly make a dent in national spending, while the payoff would be enormous. This isn’t to say that everything NASA does is cost-effective; I have been vocal about the enormously bloated and decreasingly useful Space Launch System rocket, but its delays and overruns are traceable to congressional meddling in the project. Given less pork barrel politics and better management, NASA can deliver on its promise: bringing the Universe to Earth.

With MSR we have a real shot at investigating some of humanity’s oldest and most fundamental philosophical questions. How did we get here? Are we alone? The cost to find these answers, even in the near term, is relatively trifling.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.